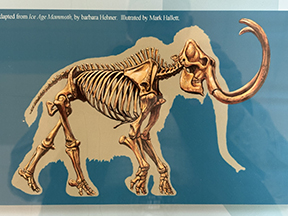

Mammoth replica skeleton at State Historical Building

IOWA has a good number of ancient animal skeletons to boast about, all in the name of science. Since the entire northern United States including the Midwest had a host of glacial ice advances during the last 2.6 million years of earth’s climatic history, ice dominated much of the time. However, it was also inevitable that in due course those glacial episodes would melt back, and thus make way for the barren raw earth soils to grow tundra vegetation at first, then in time spruce forests mixed and finally give way to grasses.

From the Bering Straits Land Bridge connecting Siberia to Alaska and northern Canada due to ocean levels at least 300 feet lower than today, the “missing” ocean water was locked up in vast northern hemisphere glaciers. Exposed land made a pathway for migration of animals in both directions.

Many species of animals big and small migrated into North America from Asia. Of those, two of the largest were both Mammoths and Mastodons. They lived during harsh environmental times and did thrive for a long time.

During my recent visit to the Iowa State Historical Building in Des Moines, upon entering its doors, my eyes were drawn to the huge skeleton of a mammoth. It is a case history that helps tell the story of our Iowa landscape long before humans began to dominate.

The mammoth lineage can be traced back to Africa, then to Europe, Asia and then to North America. Mammoth specimens did quite well over vast time frames to find grasses and other things to eat as far south as Florida, Texas, Arizona and even southern California. Columbian mammoths did migrate as far south as Nicaragua and Honduras.

Further north at the Wrangle Islands in the Siberian Arctic Ocean, mammoths lived up to about 3,700 years ago. St. Paul Island in the Alaskan Pribilof Archipelago had mammoths until 5,700 years ago.

Another form of mammoth swam the relatively narrow channel from southern California to the California Channel Islands, when ocean levels were lower and the channel islands were at that time just one large island labeled by geologists as Santarosae. The mammoth that adapted best to the island was a smaller version, the pygmy mammoth, who could more easily gain access to this land’s vegetation.

Other ice age animals of large size included camels, horses, sloths, shrub ox, musk ox, stag moose and, of course, bison. In particular were the long-horned bison, scientists named it Bison latifrons. It had a horn core spread of over six feet and when the outer keratin sheath material was growing, horn spreads of seven to 10 feet.

Samples and examples of these ancient bison can be found on display at museums. The North Dakota Heritage Museum at Bismark, N.D. is one place. Another is at the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge near Valentine, Neb.

There were a number of other bison species with long horn cores, however each species tended to become a bit smaller in body size and correspondingly in horn spread. A great example of bison lineages is available in Rapid City, S.D. at the School of Mines and Geology.

Iowa bison skulls of various past species that differed from our modern day bison skull occasionally show up in river or creek bed banks where high water flows open up new layers of soils. Archaeologists both professional and amateur may find these artifacts of time, artifacts of

ancient life on the prairies of the Midwest.

And if one is so inclined, I highly recommend a trip to Iowa Falls, to the Calkins Nature Center on the west side of that city. Artifacts in this museum tell a tremendous story about the ancient wildlife of our area and how human populations over time adapted to make a living off the land.

Natural history moments play out in all kinds of ways. Learning about both ancient times and modern times helps us place in perspective the relatively short time we have to spend learning about all the intricacies of native plant and animal life forms.

Mammoths are just one example of interesting ancient mega fauna to teach us things we did not know. Mark Twain said as much when he said “I never let my schooling interfere with my education.”

———

An interesting task for the staff of the Marshall County Conservation Board involves water flow, water control and beavers. Who is going to win this constant interplay of the ecosystem?

Here is a bit of the background work by the MCCB staff while surveying management needs at the Arney Bend Wildlife Area. This wildlife area has 213 acres of river bottom forest.

Within those bottomlands are numerous centuries old river channels, river oxbow courses that exist in a whiplash fashion of cutting and filling in overlapping meanders. Today, the forest hides most of these artifacts of old river channels, until a new high water or flood event helps to redefine where they had been.

Arney Bend’s wildlife species will find a long list of resident and migratory birds. Migratory birds use the ephemeral ponded water to rest and feed. The biggest yet shallowest are old river oxbow channels that tenaciously hold winter and spring runoff well into the fall.

Pelicans and waterfowl are primary users of the water. Wood ducks find lots of tree cavity nesting sites. Spring and fall song birds are common.

Furbearing animals like mink, otter, muskrats, weasels and raccoons live here. Wild turkeys and white-tailed deer use the site extensively. So do beavers, Iowa’s largest rodents.

The Arney Bend Wildlife Area was purchased in 1980 to conserve and manage a large timbered site of the Iowa River Greenbelt. A grant from Iowa’s Wildlife Habitat Stamp program provided 75 percent of the cost of acquisition.

The remaining 25 percent was raised via numerous businesses, civic organizations and individual donations. Technical assistance was provided by the Izaak Walton League of American Endowment who assisted with other private fundings.

A few of the prior open fields were seeded to native prairie grasses. It has been and continues to be well used. It is an area dedicated to wildlife.

The MCCB staff needed to replace some old metal culverts that connected and provided maintenance access. Old culverts were removed along with ages old beaver blockages this rodent group had previously piled up.

So this fall, the old culverts were removed, newer ones set in place, and drainage from wetland to wetland was restored. When the staff returned the next day to complete their finished work, beavers had worked overnight to plug up the new culverts!

Nowhere in the immediate vicinity were there any gnaw marks on saplings or trees to indicate that beaver had a close by bank den for residency. Somehow the beavers had found running water flows that they wanted to impede.

Maybe nature’s little furry rodent engineers know something we humans do not. Maybe they are just trying to save water anywhere they can in any way that they can.

Learning to live with what we may call nuisances of beaver behavior is something people will have to adapt to. If we can’t beat them, how about joining a team effort. That appears to be the compromise being called for.

———

DEER HUNTERS continue to work hard to take a critter or two. Statewide as of midweek, the deer reported harvest is well over 21,000. Over 8,000 are female deer and a bit over 13,000 are male deer. Marshall County deer hunters have reported 111 total deer.

A good number of sightings are taking place by archers. The problem is that now every sighting, in fact most visual connections, are not those within range or a short range weapon like a long bow, recurve or compound bow.

All of the archery season work is a labor of love for the outdoors. All are waiting for the right moment in time. Good luck to all.

———

“If you talk about it, it’s a dream; If you envision it, it’s possible; but if you schedule it, it’s real.” — Anonymous

Garry Brandenburg is the retired director of the Marshall County Conservation Board. He is a graduate of Iowa State University with a BS degree in Fish & Wildlife Biology.

Contact him at:

P.O. Box 96

Albion, IA 50005

- PHOTOS BY GARRY BRANDENBURG — In the area of planet earth, the Midwest, and specifically the area we call Des Moines, Iowa, once lived huge animals on the tundra landscape. This is a skeleton replica of the bones of this enormous animal. Some of its bones were encountered as the result of deep pylon drilling for large downtown buildings. Then, to add to the authenticity of what these animals looked like, a specimen from the far southeast corner of Wisconsin near the shoreline of Lake Michigan, was discovered. Its bones were 90 percent complete. Its study, while being removed, indicated that humans had butchered the beast for its meat. Thousands of years later, its bones, now mineralized but retaining their shapes during life, gave scientists another example of the proof of post glacial environments. They lived during the time called the Pleistocene epoch, feeding on river side and tundra vegetation until a naturally warming climate changed the plant life ecosystem enough to cause these animals to become extinct. The long tusks are actually teeth, not horns and not antlers.